Buddhists believe that the child is a passing guest and the mother an inn where it stops to borrow a garment before going on its way. Jan knew that motherhood can be a lifetime sentence with small possibility for parole, entered into more or less willingly, and often blindly, by the person to be sentenced.

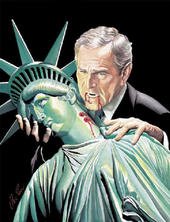

For three years, she had believed that her sentence had been commuted, that she was finally free of the hulking vampire who had sapped her energy and self respect, as well as her finances. The secret of immortality, she often thought, was, quite simply, never to reproduce.

She identified with the delicate, desert tarantulas hunted by huge black wasps, paralyzed, impregnated, and dragged underground as unwilling hosts and food for the alien young, to die when the parasites emerged, black winged, carrying their messages of horror to another generation of gentle creature toiling below them.

Her high desert home served as refuge for a number of the tarantulas, smallish beige ones, with long graceful legs and neatly tipped black feet, who repaid her for sanctuary by keeping the house free of roaches and other such pests. The tarantulas seemed to share her desire for privacy, seldom leaving the ceiling except for an occasional disastrous foray into the bathtub from which they had to be rescued. Once one of the wasps had found its way into the house and Jan had hunted down and pulverized it, startled at her own fury.

The delicate spiders made her smile and seemed to complete the circle of protection that the house spirits wove around her. Her other creatures were a timber wolf named Kali, after the fearsome Goddess, protector of the the Dharma and bringer of rebirth through death, and a graceful silver and gold bracelet of a snake, a California rosy boa named Medea. A number of scorpions had invaded over the summer, but they didn't belong. Something had always alerted her to their presence and she killed them without passion. They disappeared soon after the tarantulas moved in.

Sometimes she dreamed of the tarantulas crocheting a blanket of protection, forming a graceful lace web, like so many black and beige daisies. Their slender black feet touched and formed the outer circles of the pattern while they waited, filling the crawl space above the ceiling -- tiny guardians -- silent.

Jan had finally burned off the passions, gaining wisdom and peace. Now, at last, she had time for her own painting after a long career of caring for the work of others. At sixty-nine, she had been retired for two years from her post as a museum curator in Los Angeles. Fears that she might be lonely or miss the attentions of the partrons and staff had proved unfounded, as she bathed in the absolute quiet and serenity of the house.

Constant rambling in the desert with Kali running before her and devoted practicing of T'ai Chi had enabled her to avoid the aches and pains that might have been expected. Ten years ago, Jan had had a good face lift, so she looked and felt considerably younger than her years.

The only cloud on her horizon was Hal, her son. When she moved into the house, she had vowed never to let him spend the night. His forty years seemed to have taught him nothing. He was as miserable an excuse for a human being as he had been for a son.

She had long ago given up berating herself for his failings. Handsome and charming with an IQ of 145, Hal had no principles. She feared that he was also a coward. Her ex-husband had been an ass and certainly not a good father, but Hal's upbringing had not been so deprived as to turn him into what he was. As far as she knew, he had never repaid a debt and had victimized all of his friends, as he had her, to support whatever his current habit might be. He liked to say that he was a child of the chemical age and she privately agreed that there seemed little that was natural about him.

She had never forgotten the sinking feeling when she first held Hal in her arms and stared into his small alien face.

"I'll fix you. I'll show you!" his father had spat in rhythm during the rape in which he had been conceived. Of course, she hadn't known that it was rape, for the concept that one could be raped by one's husband was unheard of forty years ago. She'd named the baby Harold after Harold Teen, a wholesome comic strip character out of her childhood, and hoped for the best.

The experience of holding each of her daughters had been entirely different. Margie, the oldest, was sweet and passive, never any trouble, a pleasant guest but not someone that Jan had really known. With Julie, her next, came the shock of recognition. This was her child. Finally Hal had come. He was ten years old before she actively admitted that something was wrong. She tried to love and cuddle him, but it was difficult. He always seemed to be watching her slyly out of the corner of his eye, and she used to wonder if he would murder her one night. Like an alien being from a science fiction story, he had soaked up knowledge for his first ten years and then refused any further education. She would take him to school, put him in the front door and he would go out the back. He was finally expelled for non-attendance. At home, he tormented both her and the girls, his agate blue eyes glistening and darting like pirhannas in a bowl, while he plotted outrage after outrage.

Jan had had no idea how to deal with him. Her own upbringing had been gentle. Her parents were good, kind people who had hidden their differences from their children. She firmly believed in truth, integrity and decency. She had never willingly hurt another human being. Always, she had been as willing to forgive as to fight, until now.

He was back. He had called her from Barstow and asked for a place to stay for a few days...until he "got on his feet," a line that she had heard too often. She didn't want him to come and mustered the strength to tell him so.

"I have nothing for you. I don't want to see you. Please, let me alone."

He had hung up before she finished speaking.

The karmic dance whirled through her head. "You can't let him destroy you again. You can't...you can't..." The voices seemed to come from the tarantulas, from Kali and Medea, from all of the house spirits embodied in the leaves caught in the dust devils outside.

They warred on the mother side. Protection of the gene pool might be what caused parents to buckle under the onslaught of their children, but spirit had to come before biology. She would not let him hurt her again. She didn't have time. She had earned these days of peace.

She kept hearing the ominous click of the receiver. Somewhere, perhaps nearby, his cold eyes were darting, while he chewed his sparse moustache. . .and thought of her.

Her heart beat too fast. She leaned back to let the peace of the house enfold her. She needed to relax. She couldn't. Hal's malevolent face interposed between her the soothing of the spirits.

Then she was calm. Her fingers loosened on the phone. Medea coiled her way up the side of her glass prison, tongue flicking. Kali made a low moaning sound and rubbed against Jan's sweatsuited legs. Turning her eyes to the ceiling, she saw a snowy tarantula with black boots emerge from the air vent. Dry leaves skittered against the house. She was protected.

The veil lifted and she knew that this scene had been played time after time. Sometimes he won. Sometimes she. If she played it right, she might get off the wheel, might not have to return.

She hadn't sought him out. Never over the ages had she sought him out. This time the rape had been his forced entry into her life. He had always stalked her. Never had she fought back, never had she destroyed him. She must learn. If she didn't, she would die and the drama would be replayed. She would not be sacrificed again.

For a moment, she considered suicide and as quickly rejected it.

When she heard his car straining up the hill to the house, she was ready. In her hand was the .357 magnum revolver given her by her last lover.

Hal crunched to the front door through the leaves swirling around the house and rang the door bell. She didn't move. Then he beat on the door. After a few moments, he crunched around to the back. She half hoped that he would return to his car and leave, and half wanted the confrontation over.

"If he doesn't break in, I'll let him go," she told the house spirits. Kali was growling. She had hated Hal ever since he had beaten her when she was a puppy. Medea hissed and swayed, occasionally thumping the glass. It was quiet outside. Even the leaves were still. Then Jan heard sounds at the sliding glass door in the living room and knew that he had lifted it from its track. She didn't hear him replace it. She crouched behind her desk in the darkness, hands and heavy gun braced against the top. If she only wounded him, she would probably have to care for him for the rest of her life. He would have won again.

Calling her, he came to stand in the doorway under the ceiling vent. "Mother," his voice held menace. "I know you're in there."

Her hand did not tremble on the gun. She closed her eyes, held her breath to squeeze the trigger, and was stopped by his scream.

Opening her eyes, she saw him back lit, in the midst of a glistening snowfall of the exquisite tarantulas. "Oh God, get 'em away!" his voice shook with revulsion, while his hands flailed ineffectually at the life moving around his head. Her wonder at the sight was punctuated by his horror. She didn't move.

Moments later, standing at the upper window, she watched him zig zag to his car, a halo of tarantulas reflecting in the lone street light.

He would not return, this child of the chemical age.

Smiling, she looked up at the ceiling. Only the single white tarantula was visible.

Outside, dust devils, friendly leaf clad dervishes, danced through the empty space left by Hal's car.

...by

Felicia Florine Campbell

Her position was, indeed, to a marked degree one that, in the common phrase, afforded much to be thankful for. That she was not demonstratively thankful was no fault of hers. Her experience had been of a kind to teach her, rightly or wrongly, that the doubtful honour of a brief transmit through a sorry world hardly called for effusiveness, even when the path was suddenly irradiated at some half-way point by daybeams rich as hers. But her strong sense that neither she nor any human being deserved less than was given, did not blind her to the fact that there were others receiving less who had deserved much more. And in being forced to class herself among the fortunate she did not cease to wonder at the persistence of the unforeseen, when the one to whom such unbroken tranquility had been accorded in the adult stage was she whose youth had seemed to teach that happiness was but the occasional episode in a general drama of pain.

Her position was, indeed, to a marked degree one that, in the common phrase, afforded much to be thankful for. That she was not demonstratively thankful was no fault of hers. Her experience had been of a kind to teach her, rightly or wrongly, that the doubtful honour of a brief transmit through a sorry world hardly called for effusiveness, even when the path was suddenly irradiated at some half-way point by daybeams rich as hers. But her strong sense that neither she nor any human being deserved less than was given, did not blind her to the fact that there were others receiving less who had deserved much more. And in being forced to class herself among the fortunate she did not cease to wonder at the persistence of the unforeseen, when the one to whom such unbroken tranquility had been accorded in the adult stage was she whose youth had seemed to teach that happiness was but the occasional episode in a general drama of pain.